"Smoking was generally permitted, and boisterous conduct

accompanied by the throwing of material, were not

infrequent occurrences."

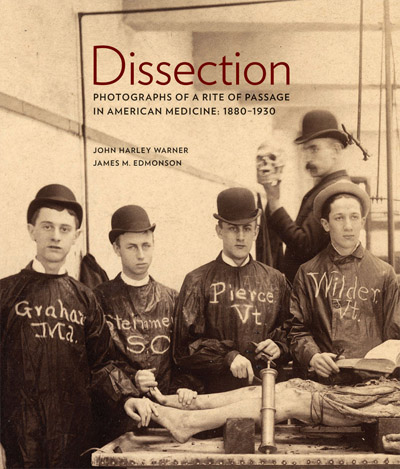

The following is a review of the recently released medical pictorial monograph titled, Dissection: Photographs of a Rite of Passage in American Medicine 1880-1930, by John Harley Warner and James M. Edmonson (New York: Blast Books, 2009. ISBN: 978-0-922233-34-2). This book is a splendid first scholarly study on the photographic iconography of dissection.

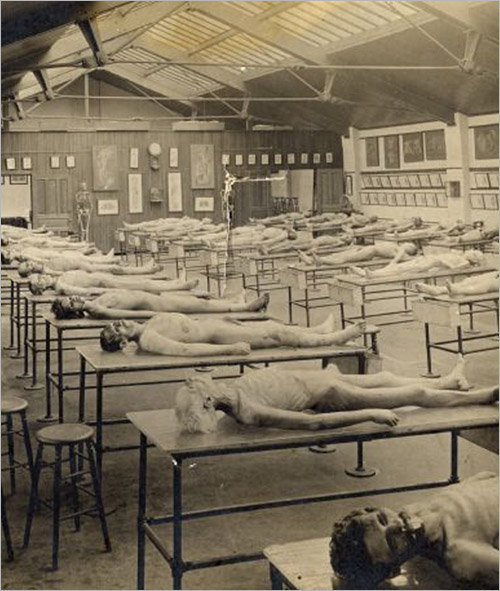

A photograph of the Rush Medical School dissecting hall (page 4) has turned my thoughts toward the Hungarian born surgeon, Dr. Max Thorek (1880-1960). The picture was taken in 1900 and judging by the inviolate conditions of the 28 cadavers that are laid out on identical gurneys it was taken a day or two before classes were scheduled to begin. At any moment Thorek will walk through the door, pick up his scalpel, and start his first preparation. In his autobiography, he tells the story of a rough encounter with the dead bodies who matriculated alongside him that year:

Suddenly I felt a new note in the silence around me. We had not been talking as we worked, but this quietness had no companionship in it. It was different, and somehow disquieting. I looked around. I was alone. I went to the door. It was locked. The wretches who pretended to be my friends had locked me in to spend I did not know how long in the gruesome company of the dead. Now a cadaver is not altogether a helpless thing. A good cadaver has ways and means within itself to startle the living daylights out of a man. And a dozen cadavers, such as were now ranged around me, could be expected to multiply the surprises and shocks if their mere presence did not unnerve me. [2]

Thorek was remembering the experience of a hazing by classmates who had locked him up in this room. He was trapped for less than an hour, but it was long enough to disturb his dreams that night with visions of the dead people he was about to cut open. Their tongues suddenly reanimated and gave voice to horrors such that cannot be spoken by tongues that are attached to anything living. The new Prince Albert suit that Dr. Thorek wore for his matriculation at Rush did not survive the first week of hijinks, but from that fire he emerged as one of the 20th century's great humanist surgeons.

The Rush photograph was not conceived in ambiguity. The motivation was one of institutional identity, a proud administration's desire to showcase the school's resources and its rich endowment of anatomical material. It states that Rush should be counted among the first tier medical schools in America which were first to adopt the modernization reforms begun by Charles Eliot (1834-1926) at Harvard in 1871 and—specific to anatomical facilities—Franklin Paine Mall (1862-1917) at Johns Hopkins.[3]

However, a more thoughtful examination of the Rush photo and the photographs from the Dittrick collection presented in this book will yield evidence of the absolutism of medical education at the time—the institutional power to suppress any and all resistance and discomfort caused by gross anatomy programs. This suppression of dissection horror is the legacy of Vesalius who substituted an elite and dynamic scholarship for the ecclesiastical errors of Galen and until recently, medical men did not tolerate interference by a horrified public outside the walls of academia—those ignorant folk who refused to give up their dead to the insincere placations of a provost and to the knives and tenacula of a fumbling novice. Hazing and hijinks also made quick work of vestigial scruples within those walls. The grinning death head of a student who tugs on the male organ of a cadaver (page 146) is flaunting a proxy of his own penis and soldiering for medical science.

The suppression of dissection horror as a strategy for advancing medical science came undone in Germany during World War II. Much as I enjoyed the excellent synopsis of the history of dissection provided by Warner and Edmonson in their monograph, the omission of any reference to the work of Dr. Robert Jay Lifton is puzzling. It was also omitted from Michael Sappol's history, A traffic of dead bodies,[4] which has become an important resource on the subject. Dr. Lifton's research into the behavior of physicians under the Nazi regime revealed a direct correlation between the socialized suppression of dissection horror and the formation of a professional identity that is dissociative and capable of the atrocities committed in the clinics of the concentration camps:

That doubling usually begins with the student's encounter with the corpse he or she must dissect, often enough on the first day of medical school. One feels it necessary to develop a "medical self," which enables one not only to be relatively inured to death but to function reasonably efficiently in relation to the many-sided demands of the work. The ideal doctor, to be sure, remains warm and humane by keeping that doubling to a minimum. But few doctors meet that ideal standard. [5]

Lifton's work framed the question underlying why most medical students like Max Thorek can emerge from gross anatomy with their humanity intact, while a certain few become monsters. A reading of Lifton is sine qua non for an understanding of why and how the age of Vesalius, which set dissectors apart and above the rest of society, is now evolving into the age of the Visible Human Project with its many shades of participation. Lifton is also essential for an understanding of why today an iconography of dissection finds its reception in complexity, why an image of a dissector mounted on an Easter card (page 125) can look so darkly beautiful and at the same time, so wrong.

1.) Bardeen, Charles Russell (1905), Anatomy in America. Madison: Bull. U. of Wisc., no. 115.

2.) Thorek, Max (1943) A surgeon's world; an autobiography. New York: Somerset Books ; pp. 66-67.

3.) Bardeen, page 171.

4.) Sappol, Michael (2002), A traffic of dead bodies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

5.) Lifton, Robert Jay (1986), The Nazi doctors. Medical killing and the psychology of genocide.

New York: Basic Books Inc.; pp. 426-427.